Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

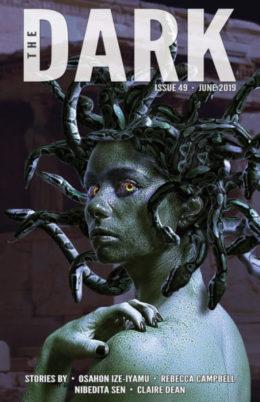

This week, we’re reading Nibedita Sen’s “We Sang You As Ours,” first published in the June 2019 issue of The Dark. Spoilers ahead—but go ahead and read it yourself; it’s short and awesome.

“Maybe you should be scared,” Chime said. “If you mess up the hunt, Dad might eat you too. Just like he ate Mother Aria.”

Summary

Cadence, and her little sisters Bell and Chime, kneel by a bathtub filled ten inches deep with seawater. The jellyfish-like egg floating in it, according to Mother Reed and Mother Piper, will be a boy. Chime prods the egg, saying she bets they could smash it. Cadence reprimands her, but thinks about it herself, “that gluey shell crumpling, blood and albumen flooding the tub.” She doesn’t know, though, “what was folded in the egg’s occluded heart, dreaming unborn dreams.”

Bell reminds Cadence she needs to be dressed when Mother Reed comes home to take her on her first hunt. Chime teases that Cadence is scared—she’ll be meeting Dad for the first time, and if she messes up the hunt he might eat her, like he did Mother Aria. Cadence, enraged, shouts that Mother Aria didn’t get eaten; she left them and isn’t coming back. Chime sobs, Bell sniffles. Two weeks ago, before Aria left, Cadence would have been good, comforted them. Now she’s found a new self who doesn’t want to be good.

Cadence believes she was Mother Aria’s favorite, the frequent recipient of Aria’s lop-sided, somehow conspiratorial smile. Aria was always a little different from the other two mothers. Maybe they should have seen her disappearance coming. Maybe Cadence should have seen it, that last night when Aria came to her bedroom and sang her the song without words, the song of the waves. Though mothers are only supposed to sing-shape children in the egg, maybe Mother Aria sang something into Cadence that night to make her different too. Something to make her sick at the thought of her first hunt instead of excited.

Mother Reed drives Cadence to the boardwalk and lets her out: Tradition demands that she hunt alone. It’s stern tradition, too, not to speculate which mother laid one’s own egg, but Cadence can’t help but think Mother Aria laid hers, for they have the same looks. Stupid idea. Looks come not from one’s mother but from whomever Father ate right before fertilizing the egg.

She heads down to a beach crowded with humans. A child runs by, but Cadence shudders at such easy prey. Then she bumps into a boy her own age, Jason, who seems a more appropriate object. They converse, Jason doing most of the talking. It’s easy to lure him, just as Mother Reed has promised.

As dusk falls, Cadence leads Jason to a deserted stretch of beach. He’s about to answer a call from his dad when she begins singing without words. Her kind don’t sing sailors to their deaths from rocks anymore, but the song’s unchanged.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Entranced, Jason follows Cadence into the surf. She locks her elbow around his neck and swims out far, dives deep, her song becoming “a submerged dirge.” Jason starts writhing in panic—where’s her father? Didn’t he hear her singing?

There. Her father rises, “barnacled shell trailing shreds of kelp,” beating his great tail. Beside him, Cadence is tiny, no longer than one of his “lobstered legs.” Don’t stay to watch, Mother Reed has warned, so Cadence releases Jason and swims away from her father’s “dead-fish stink, and underneath the shell, the shadows and suggestions of his terrible face.”

She can’t see Jason’s blood in the dark water, but she can taste it.

Back home, she retreats to her room. When Mother Reed comes up, Cadence asks why she and Piper don’t just leave Father, pack them all up and go. It’s hard being the oldest, Mother Reed sympathizes. But Cadence must lead her little sisters, for the three of them won’t always live with her and Piper. They’ll someday start a new nest with their brother, who’ll father their daughters. The Mothers have sung Cadence to be obedient, unlike Aria. Cadence won’t desert her family like Aria has.

The next day, however, Cadence digs through a jar of shells she and her sisters collected and finds the hoped-for note from Aria, simply a phone number. She ponders how she never knew Aria as a person—how she never imagined Aria could want to be free of her. She ponders what she did to Jason, how she’ll have to kill another human every week now, as her mothers do. Because what if they stopped doing it? Would Father emerge, rampage on his own?

Is there a world beyond the taste of blood in the water?

Cadence fills a backpack. At night, her sisters asleep, she creeps with it into the nursery bathroom. She could break the brother-egg, but that won’t get rid of Father or prevent her mothers from laying another brother-egg that Cadence’s sisters would one day have to serve. Without Cadence.

She kneels and touches the gelatinous floater. It pulses under her palm, “heartbeat or recognition.” Bell and Chime pad in. Are we gonna smash the egg, Chime whispers excitedly. Bell looks toward Cadence’s backpack, by the press of her lips already resigned to betrayal.

Come in, Cadence signs. But no, they’re not going to smash the egg bobbing in seawater, “rich in blood and albumen and potential, waiting to be sung into shape… waiting for them to make it into something their mothers had never dreamed.”

No, Cadence says. “We’re going to sing to it.”

What’s Cyclopean: There are lines like poetry, young sirens learning to swim “slipstreaming through the murk with their kelp-forest hair fluttering in the current, counting summer flounder on the seabed,” and the siren song itself: “of ocean mist and white sails, crying gulls and deep water.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Sirens don’t seem to make much distinction among various groups of humans, aside from “close to the water” and “too far away to catch.”

Mythos Making: Strange creatures lurk under the waves, waiting for human blood. And those who feed them lurk closer to shore, unrecognizable until it’s too late.

Libronomicon: No books, but the mothers use DVDs of high school dramas to teach their offspring how to act human.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Cadence thinks there must be something wrong with her, not to be excited about her first hunt.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Some horrors are terrifying because of their difference. They’re unnameable, indescribable, or simply so far from any familiar form that it’s painful just to know they exist. Some things, though, are terrifying because of their similarity to humanity. Deep Ones may look odd, but they pass in ordinary society. The Yith cloak themselves in human bodies. Mermaids mimic human faces and voices, tempting us near enough to become prey. The predator you think you know is often the most likely to get you.

In terms of predatory adaptations, Sen’s sirens aren’t too far off from Grant’s mermaids. They look like us—a lot more like us than the mermaids, actually, enough to walk freely on the Rockaway Beach boardwalk. Enough to flirt with a teenage boy, and tempt him into the water. There’s enough power in their voices to tempt an unwitting human to their doom. And like Grant’s mermaids, they have a… dramatic… level of sexual dimorphism.

For those drawn into the water, the exact nature of the thing that eats them may not make a lot of difference. For those of us reading on the beach, on the other hand, it matters. Grant’s underwater horror is the monstrous female. It’s an archetype of longstanding history, repeated in literature ever since the first patriarchal poet looked at the constrained life forced on the women who made his poetry possible, and imagined gorgons living beyond the civilization’s bounds. Written well, she can be terrifying even to those who think civilization might survive a hint of women with power, or empowering to those who’d like to break a few constraints.

Sen’s horror is the monstrous masculine. More familiar in everyday life, he’s the creature who won’t just swallow you whole and bloody, but will shape whole families and societies to make sure he gets his fill. Who’ll make you complicit in his predations. Who’ll insist the rules that feed him are the only possible rules to follow. And one of the monsters that we still don’t quite know how to defeat, opening space for stories that might help us figure it out.

I have so much literary analysis squee about this story, because the Half-Visible Underwater Monster That Eats People And Is Also The Patriarchy feels like a thing that’s very much needed in the discourse at this particular time, and because I want to be able to go up to people and organizations offering subtle-yet-destructive messages and instead of providing incisive analysis that they really haven’t earned just be able to say “YOU. YOU ARE SINGING PATRIARCHY-MONSTER-FEEDING SONGS, CUT IT OUT.”

But I also don’t want to drown everything in literary analysis, because I also love the close-up family drama of teenage sirens trying to deal with one of their moms having run off and the stress of a new sibling on the way, and questioning their traditions and trying to figure out their own moral compass. And I do adore me some human-side-of-the-monster stories where you peer past the sacrifice and the killing and see someone a great deal like you on the other side. I didn’t realize I was hungry for stories about monsters who question those monstrous things they’ve been raised to take for granted, and who try to find an alternative.

And here’s where Sen brings the symbolic and the literal together. Her answer to patriarchy-monster-feeding songs is as gorgeous as everything else in this story: new songs. New ways of caring. Not taking for granted that children must grow into their parents’ monstrousness—and using all our arts to help them find new ways.

Anne’s Commentary

In Nibedita Sen’s “Leviathan Sings to Me in the Deep,” it’s whales doing the vocalizing, as well as sailors transformed through the power of whale-song into the very prey they used to hunt. Born whales and homocetaceans alike worship Leviathan, a being whose eye alone is bigger than the whalers’ ship. The verb “sing” in the title isn’t the only echo between this story and “We Sang You as Ours”; in them, song functions both as communication and magical force, with legendary sea beings as the vocalists and a vast watery creature as their deity in fact or effect.

I liked “Leviathan.” I love “We Sang You as Ours.” For me it was a gift basket crammed beyond seeming capacity, its contents ranging from amuse-bouches of description and detail to challenging thematic entrees. So much to unpack and savor.

As we’ve often seen authors do in this series, Sen examines the Others from their own point of view. It’s not the first time we’ve encountered the siren—remember Mira Grant’s Rolling in the Deep? A big difference between the two is that Rolling is written from the human perspective, with its mermaid-sirens very much Other: monsters in the classical sense of the word, terrifying and utterly inimical to mankind, their natural prey. A big similarity is that Sen and McGuire imagine extreme sexual dimorphism as a defining feature of their sirens’ biology and hence lives. McGuire’s dominant sex is female, one enormous “mother-queen” supported by many far smaller males. Sen’s dominant sex is male, a “brother/father-king” supported by a handful of far smaller females.

Given Rolling’s human point of view, it’s unsurprising that we see its sirens more as subjects of a (very dark) nature documentary than as a species as intelligent and emotionally complex as ours. The opposite is true of the “We Sang You” sirens; Cadence’s intellectual and emotional complexity is a central strength of the story, and each of her mothers and sisters has a sharply defined personality. It could be that McGuire’s male sirens vary in personality. It could be some of them chafe under their biological constraints, even rebel against them. But the human characters don’t see this. I should say, they haven’t seen it yet; McGuire’s sequel novel, Into the Drowning Deep, hints that humans may yet plumb her sirens’ psychological depths.

Maybe as much as they want to plumb them. It would be fine if McGuire’s sirens remained unsympathetic, alien-scary. Like, say, the Color out of Space, the Flying Polyps, or the Shoggoths. A common complaint about latter day Mythosian fiction is that it makes the monsters too relatable. Too “human.” Therefore way less scary. I can understand that viewpoint, but I don’t share it. For me, the more “human” the monsters get, the scarier they are.

Come on, we humans can be a hella horrifying lot.

Sirens, Cadence tells us, are not human. Okay, that’s scary. Big however: At conception, every siren inherits the looks of the last person Dad dined on. Or so Cadence has been told. An idea that impresses her more is that she’s also infused with the essences of everyone he (or perhaps her species) has ever eaten. So whereas a conscientious siren might want to lead only jerks to their deaths, she wouldn’t want to have only jerk-influenced children. It would be simple if she only had to worry about snagging a handsome victim just before mating with Dad. Much more complicated, ethically and practically, that she has to decide between sparing good people and selectively hunting for good people in order to secure premium raw material for her eggs. Sure, she and her sisters get to manipulate the raw material. But it’s got to be a lot tougher to sing-sculpt offspring from rotten timber than from fine marble.

Question: If sirens are monsters, is it because humans have made them so? Question: If sirens are on the whole content to go on serving their still more monstrous fathers and brothers, is it because they’ve inherited the tendency toward social inertia from humanity?

Scariest question of all: Could snaring victims for Dad serve the sirens’ own desires? For all her initial reluctance, Cadence feels a “deep and pleasurable ache” in her throat as she sings to Jason, a “dark, hot lick of excitement” as she leads him into the sea. His adoration is a thrill; so, too, her sense of power in creating it, in mastering him. In being beautiful. Irresistible. A—siren!

Is the pleasure worth delivering the adoring one to slaughter? Worth tasting the adoring one’s blood, when blood is bitter to you? Worth killing as a weekly routine when you don’t have to? Escape is possible, as Aria’s proven. But escape means leaving mothers and sisters behind. Betraying your duty and love for them.

Is there a solution? Sen’s conclusion is hopeful. Aria may have sung a deeper rebellion into Cadence than the urge to run from unendurable expectations, because Cadence chooses to stay and to try to change those expectations, to sing-shape with her sisters a new kind of brother, a new social structure.

And may their singing birth some fine revolutionary anthems, too!

Next week, we celebrate the start of summer by signing up for a special course at Miskatonic University, with David Barr Kirtley’s “The Disciple” as required reading. You can find it in New Cthulhu: The Recent Weird, available at the campus bookshop.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.